☞ The Technological Parentheses of Our Lives

My daughter used to pay very careful attention to my driving. But it wasn’t really just about road safety or even sightseeing—it was about information. She noticed landmarks and streets, she asked about road signs, and she carefully watched traffic lights. All of this was because, as she happily informed me, she wanted to be ready to drive when she was older. Her excitement for this milestone many years away was infectious, and all of this attention and learning was in service of this goal. But all I could think about when she would tell me this was that there was a decent probability that she would never have to learn how to drive. With all of the developments and buzz around autonomous driving (though this promise continues to recede into the future), she may never need to learn how to do this. Something that requires hours of practice and has been a rite of passage for American teenagers for decades might simply evaporate from our culture. This skill could very well end up going the way of the finer points of mastering the buggy whip. Or—post-pandemic and its technology-mediated shopping—the skill of purchasing items in a store in-person.

Or even mastering the dial tone.

In the mid-1950’s, to prepare users for the completion of the switch from telephone operators connecting calls to rotary dialing, AT&T made a film all about how to use a rotary telephone: Now You Can Dial (I discussed this film previously awhile back). The film explains the details of a rotary dial, what a busy signal sounds like, and the nature of the dial tone, among other features. It even, bizarrely, recommends that people “wait for at least a minute, or about ten rings,” for someone to answer before hanging up.

But here’s the thing: for many younger telephone users, these features are vanishing. If you’ve only ever used a smartphone, you might never have even heard a dial tone.

The passage of time means inevitable changes in technologies. Some of these are small: I doubt many people lament the absence of calculator watches or floppy disks. But other changes are far larger. And they don’t just provide elements of nostalgia for period pieces on prestige television, they infiltrate numerous aspects of our lives. When one of these technologies evaporates—such as driving a car or telephones that sit on a table or hang from a wall—it can rewire how we think about the world and our place in it.

These larger technological changes almost swamp our ability to even fathom a period beforehand. As someone from the so-called Oregon Trail Generation, I can remember times before widespread Internet access, how I used the library and its card catalog, navigated our telephone books, and even called a particular telephone number to receive the exact time of day when I needed to reset our clocks after a power outage. But I also can't. It’s hard to remember—and imagine—what this world was like, because it has been overwritten so thoroughly by the one we currently live in. While I can recall the experience of my local librarian helping me first use a card catalog, I also struggle to remember the details of how to actually navigate it, so thoroughly has my usage of computerized catalogs overwritten this skill. That world, so close and yet so distant, is difficult to imagine oneself within. It is truly a case where “the past is a foreign country.”

We live through technology in timespans, periods of time when something is widespread, taken for granted, and seemingly the natural order of things. Yet these are all ultimately ephemeral.

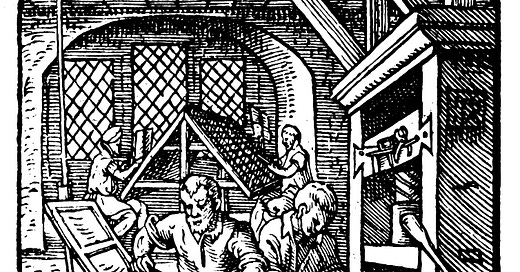

To understand this a bit better, we can look even further back historically, beyond the nostalgia of recent technologies, to the printing press. In the folk telling of media history, prior to the printing press, the oral word was paramount, while writing and reading were rare and special. These were the skills of the educated elite, the scribal classes, the nobility. But then, as a result of the printing press, these activities were democratized and became widespread. Print had a great several-century-long run, and to be fair, it’s still going strong. But with the advent of digital technologies and the Internet, print is again receding in its preeminence and a more oral sort of Internet culture has blossomed (though literacy is very much here to stay). The argument, then, is that this period of several hundred years when print media reigned, far from being the default state of civilization, was rather the “Gutenberg Parenthesis”: an evocative phrase for a singular period of time, a kind of interruption by print culture of the much longer—and perhaps more natural—oral culture.

While I will make no such grand claim for the telephone, I’d like to stretch the metaphor to the point of misuse: I think we are living at the very end of the Dial Tone Parenthesis, as well as the Driving Parenthesis, and Compact Disc Parenthesis, and so many more of these Parentheses, specific time periods when these technologies were once paramount.

These technological parentheses all point to something fundamental about society: even though humanity is really good at dealing with change, we are bad at anticipating it. We are always living within a whole cluster of parentheses, but too often we are completely oblivious to this state of affairs and almost never think about anticipating their ends. Even though we intuitively know that technology is always changing, we still think of individual skills necessitated by categories of technologies as long-lasting or ever-present. We might recognize that cars will improve, but there is a big difference between not having to manually roll down windows any longer or fiddle with a cassette player, and not having to even know how to drive anymore. Information storage methods have changed a lot since magnetic tape and floppy disks, but we are still used to the idea of storing information, even if it’s on the cloud. But being able to anticipate when basic skills will be rendered outdated is something we are ill-prepared for. We are in an ever-present state of technological prelapsarianism, forever unable to recognize that the technologies around us—and the society that they describe and create—are in a continuous state of future obsolescence.

Each technology’s loss has a cascade of effects, from the small—the specific procedural knowledge involved in mastering a skill, such as the logarithmic nature of a slide rule—to the large—how we structure society around these technologies, or even simply how technologies make us feel. Returning to the potential impending disappearance of drivable vehicles, there is a joy to driving a car down an open highway or along a winding coastal road, or simply the broader freedom that cars can instill in each of us. To be clear, this is not really for me—I welcome our autonomous driving overlords, don’t particularly enjoy driving, and until a few years ago, I was driving a beat-up rusted-out twenty-year-old Buick and felt no gaping hole in my emotional life —but for many, this is a big deal. For many drivers, there is profound emotion tied up in their vehicles, and if this skill were to vanish—along with the emotional resonance around teaching your own children to drive—something would be lost.

But here’s the thing: the very failure to anticipate the endpoints of these parentheses means that we are certainly living in many of these right now and are simply ignorant of them. Yes, driving gets the headlines, but there are no doubt so many more of these parentheses that surround us, but to which we are blind. What would these look like, these everyday technologies that we take for granted but may one day vanish? Well, they would have to be part of the fabric of our technological lives, so embedded that they could be used in the plots of our sitcoms, yet might be as puzzling to those in the future as the finer points of telephone answering machines in episodes of Seinfeld are to today’s youth.

So, other than driving, which we are often told might be on the verge of vanishing, what are the other large technological parentheses are we living in? Are we near the end of the skills required to read a map, as Google Maps and its brethren render the knowledge around what a map legend no longer necessary? Will the details and etiquette of ringing a doorbell go away, as today’s youth simply opt to text when they are outside?

There are a lot of potential parentheses to speculate about, from the end of fossil fuels or eating meat as a society, to the end of screens due to augmented reality (this could have implications for the arrangement of our homes, as Joey from Friends asked of someone without a TV, “What’s all your furniture pointed at?”).

Or what about speaking a foreign language? With advances in machine translation and voice recognition, are we that far away from the universal translator of Star Trek and the uselessness of actually needing to lean foreign languages? Of course, a language is more than vocabulary and grammar embodied in some machine learning algorithm; it’s the accretion over time of how a people thinks, its culture, its ideas. But for communicating quickly, or closing a business deal in a foreign country where you don’t speak the language, maybe all you need is a good enough universal translator, a technology closer to reality than we might realize.

On the other hand, there are certain skills that seem like they might vanish but somehow stick around, like reading an analog clock. Analog clocks should have disappeared a long time ago, back in the Apollo era, and yet they remain. This one should just be a matter of time, but like a mechanical coelacanth, it keeps on hanging on. But overall, we are surrounded by these parentheses, ones that we are near the end of, and yet blissfully ignorant of them. There was even an article in the Wall Street Journal back in May 2019 by Joanna Stern on “The Tech My Toddler Will Never Know,” which included everything from credit cards and keys to dedicated cameras.

Of course, humans are pretty adaptable. We’ve gone from viewing the iPhone as a magical device from the future to something we get annoyed about all the time because it does not quite perform the exact way we wish. We have lost the wonder for this new technology, as well as all the little details of the past that were bound up in an age pre-iPhone. Each change causes a lost world to evaporate from our minds, whether it’s how to give someone driving directions prior to GPS-enabled smartphones or even the right number of rings to wait before hanging up.

The computer scientist Alan Kay famously noted that “Technology is anything that wasn’t around when you were born.” Too often, we’re blind to the sheer amount of technology that’s all around us, if it doesn’t have that whiz-bang new feel to it, whether pencils, toasters, books, or even windows. All of this is technology. But so too are we blind to the fact that each technology that we’re steeped in might be far from permanent. They have expiration dates. Whether invented before or after we were born, it’s time we start thinking a bit more about the inherently ephemeral nature of our technology, and the present that will soon be nothing more than a foreign country.

I have a new article in Tablet Magazine about how to think about organizations designed for the long-term, using insights from Judaism: “The Way-Forward Machine: If we want to plan millennia ahead, we should ask how Jews have always done it.”

And here are a few interesting articles I recently came across:

A glint in the eye: photographic plate archive searches for alien visitations

Combinatorial innovation and technological progress in the very long run

Until next time.