☞ The iPhone and the Wonder of Computing

Sparking Delight in Technology

In the course of working on my forthcoming book (which you can now preorder!), the following little remembrance of the iPhone’s release found itself on the cutting-room floor, but I thought a version of it might be of interest to readers.

Soon after the iPhone’s release in 2007, I went to a mall in the suburbs of Buffalo to see this new device in all its glory. I was home from graduate school, and together with my father and grandfather, went to our local Apple Store and stood amidst throngs of fans, hoping to see for ourselves the seamless blending of “an iPod, a phone, and an Internet communicator” promised to us by Steve Jobs. When we finally got a turn, my father removed it from its pedestal and played with it.

My grandfather, who lived to the age of ninety-nine, was an avid science fiction reader his entire life. He read the novel Dune when it was serialized in a magazine, as well as Popular Science magazine for over seventy years—for he loved the facts of science as well. He subscribed to one of the flagship science fiction magazines Analog Science Fiction and Fact for years (and gave me shopping bags of old issues when he was done with them).

After watching his son—my father—pinch and swipe his way around the iPhone’s screen, my grandfather proclaimed something to the effect of “This is it! This is what I’ve been reading about my entire life.” For him, bringing human knowledge to your fingertips was not a device for imagined interstellar explorers; it was real and it was for all of us.

But we too often forget the extent to which the smartphone is an object of magic. We complain about the locations of the tabs on our phone’s browser, or how the camera doesn’t focus properly, or how it drives us to distraction. But the smartphone is an object from our fantasies, rife with unbelievable abilities. There is the beguiling touchscreen that can register our fingers as they dance across a piece of glass, something that was hard to picture as a possibility outside of Star Trek even on the eve of the iPhone’s release. (In fact, over a decade ago, I went to an exhibit of Star Trek props at a science museum and realized that what the crew of the Enterprise-D was working with hundreds of years in their imagined future are bad versions of the iPhones and iPads we already have.)

Both grumbling and wonder are found throughout the computing world. Sometimes the grumbling is even fair (don’t use your smartphone too much!). But I think that more and more, the grumbling about the tech world is most of what we focus on, at the expense of computing also being a cause for wonder and delight, as exciting as it was for my grandfather in the Apple Store many years ago.

Returning to the iPhone, its capacity to spark wonder is intimately connected to the its ability to meld ideas from numerous different domains: around human interaction, how we listen to music, how it connected us to the world’s knowledge, how we think about information, and much more. To borrow another phrase from Steve Jobs, at Apple’s core was “technology married with the liberal arts.”

Of course, this broad view of computing and technology—one that is capable of sparking wonder—is not Apple’s alone. It is found all throughout the world of computing, but only if we choose to look for it. (And spoiler: that’s what you’ll find in my forthcoming book.) ■

Miscellanea

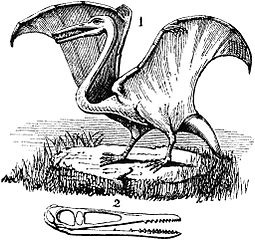

From Charles Kingsley in The Water-Babies:

Did not learned men, too, hold, till within the last twenty-five years, that a flying dragon was an impossible monster? And do we not now know that there are hundreds of them found fossil up and down the world? People call them Pterodactyles: but that is only because they are ashamed to call them flying dragons, after denying so long that flying dragons could exist.

The Tiny Awards results are out!

I recorded a podcast episode on “The Intersection of Science Fiction and Reality.”

And The Orthogonal Bet podcast series is going strong. Go give it a listen.

The Enchanted Systems Roundup

Here are some links worth checking out that touch on the complex systems of our world (both built and natural):

🜸 Curious George and the case of the unconscious culture: “For me, this was a perfect example of a creeping high strangeness I’ve noticed in the 21st century. A strangeness I don’t remember from my youth, the world of the 90s and early 2000s. Funnily inappropriate Curious George stickers are merely one instance, a symptom of something larger.”

🝳 Measuring the Black Death: “Reports suggest that between 40 and 60 percent of the population died during the bubonic plague that swept through Europe in the mid-1300s. What accounts for this wide range of estimates?”

🝤 Cliopatria: A geospatial database of world-wide political entities from 3400BCE to 2024CE

🜹 The Bright Sword by Lev Grossman: A fantastic story set in a version of the world of King Arthur. I found the layering of gods from different times and places particularly fascinating.

🝊 Vanishing Culture: On 78s: “The period of 78s doesn’t just parallel other historical developments. The sounds on 78s document cultural norms, performance practices, tastes, and the interests of people who, after centuries of drudgery and lives spent in the fields and hard labor, finally had free time.”

🜸 In Praise of Reference Books: “Reference volumes should be valued as least as much as fiction and other nonfiction books”

🝖 The Mercy of Gods by James. S. A. Corey: “From the New York Times bestselling author of the Expanse comes a spectacular new space opera that sees humanity fighting for its survival in a war as old as the universe itself.”

🝊 Productivity Is a Drag. Work Is Divine: ‘What Americans colloquially call “work” divides into two categories in ancient Hebrew. Melakhah connotes creative labor, according to early rabbinic commentaries on the biblical text. This is distinct from avodah, the word used to describe more menial toil, such as the work that the enslaved Israelites perform for their Egyptian taskmasters as described in the Book of Exodus.’

🝳 Who’s the Dodo Now? A Famously Extinct Bird, Reconsidered: ‘By the 18th and early 19th centuries, the remaining dodo specimens were so poorly preserved that some prominent rationalists questioned whether the bird had ever existed or if it was just an elaborate hoax. “The dodo and the solitaire were considered to be mythological beasts,” said Mark Thomas Young, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Southampton and lead author of the paper. “It was the hard work of Victorian-era scientists who finally proved that they were not.”’

🜹 The Searchers: “Dave Eggers on NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab”

Until next time.