☞ The Linnaean Instinct and List-Making

The Philosophy of Catalogs, Technological Archaeology, and More

Cataloging and organizing the world is a deeply human endeavor. We want to understand everything around us. In the biological world, “the task of identifying and describing all living species” has been described as the Linnaean enterprise by E. O. Wilson (the term was also used here).

But more broadly, there is the Linnaean instinct: the instinct to organize our surroundings. I am particularly sensitive to this instinct, as seen by my ever-growing collection of lists.

Perhaps there is a deeper philosophy here behind this Linnaean Instinct. First of all, it is the first step in organizing what we know. Before we can unify ideas together, or provide some sort of large conceptual framework, we need to at least have gathered and organized the facts and data. It is the precondition for any larger theory.

This Linnaean instinct—at least as I view it—is also a halfway point between hedgehogs and the foxes, as per Isaiah Berlin (and Archilochus before him): those who know one big thing and those who know many things. Creating a catalog or a list involves frameworks and organization, but it is also at peace with the grab-bag and the miscellaneous. It is a means for creating order while still being wary of too much order—or at least comfortable sitting with a bit of a mess.

It is also a means of learning from what has come before us, for to create a meaningful catalog involves knowing the history of a domain.

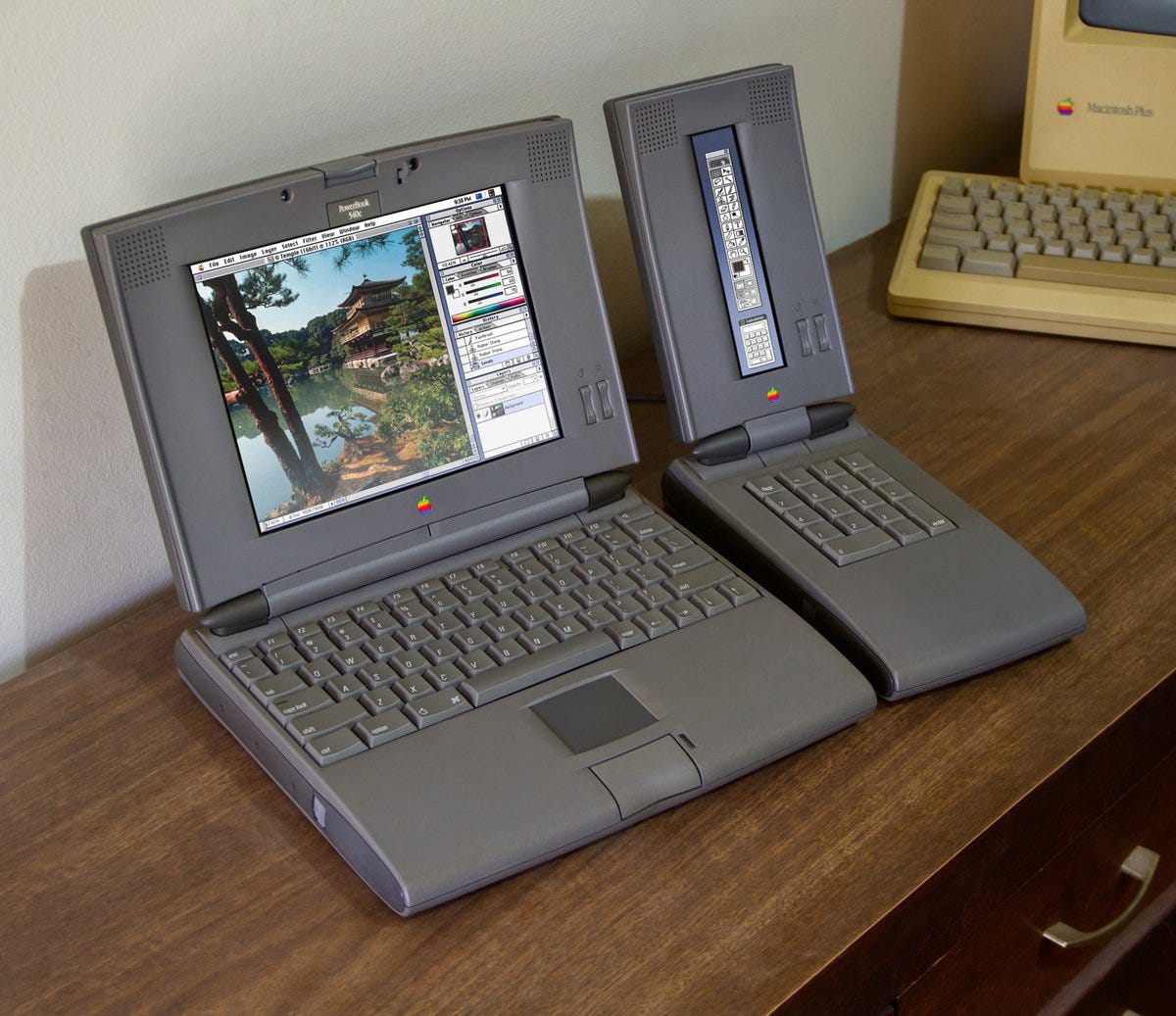

For example, technological archaeology—spelunking within the history of technology—is not just fun, it can also be a way of avoiding reinvention, or even getting stuck in the path dependence of historical choices (here’s my paean to technological archaeology). And this Linnaean instinct in technology allows us to manage technological history and to learn from it. It’s a prerequisite for learning from what has come before us. You first need to collect and organize old hardware and software (such as here or here), or even computers from alternate universes, from all the paths not taken.

All of this allows us to draw Venn diagrams around disparate themes and trends within technological history, organize them, and then use that as the basis for moving forward and building new technologies.

The Linnaean Instinct is also important for new and emerging communities. This instinct allows someone to be content living in a certain amount of chaos, which is particularly important when a scene or subculture is new. It allows you to catalog and explore—David Lang has written about the importance of catalogers in scenes and subcultures—or even find relationships between different subcultures (such as my Garden of Computational Delights), an important feature of catalyzing change.

Cultivate the Linnaean instinct. It is vital for both the new and the old, the mess and the lists. ■

Related to my Multiplayer Mandelbrot essay from last month, I came across this delightful passage in an article about researchers studying the Mandelbrot set:

To hear mathematicians tell it, computers have allowed them to treat the Mandelbrot set like a city — a physical space to explore. They’ve spent hours, days, years strolling its neighborhoods and streets, getting lost, familiarizing themselves with the terrain. “You start to understand more and more and more, and every time you come back, it’s like coming back home,” said Luna Lomonaco of the National Institute for Pure and Applied Mathematics in Brazil. “It really becomes part of you.”

Let’s find more ways to stroll through these mathematical spaces together!

The Enchanted Systems Roundup

Here are some links worth checking out that touch on the complex systems of our world (both built and natural):

🜸 Making a PDF that’s larger than Germany: “Eventually I ended up with a PDF that Preview claimed is larger than the entire universe – approximately 37 trillion light years square. Admittedly it’s mostly empty space, but so is the universe.”

🝳 Choosing a Name for Your Computer: “In order to easily distinguish between multiple computers, we give them names. Experience has taught us that it is as easy to choose bad names as it is to choose good ones. This essay presents guidelines for deciding what makes a name good or bad.”

🝳 Fluke: Chance, Chaos, and Why Everything We Do Matters by Brian Klaas: “The book’s argument is that we willfully ignore a bewildering truth: but for a few small changes, our lives—and our societies—could be radically different.” I’ve already added it to my list of modern wisdom literature.

🝤 The history of Comic Sans: “Comic Sans was meant for screen-use only, and due to the technical limitations in the mid 90s, Windows didn’t have anti-aliasing technology, which meant fonts were pixelated – as a result most fonts looked jagged and sharp.”

🜹 Vesuvius Challenge 2023 Grand Prize awarded: “There was one submission that stood out clearly from the rest. Working independently, each member of our team of papyrologists recovered more text from this submission than any other. Remarkably, the entry achieved the criteria we set when announcing the Vesuvius Challenge in March: 4 passages of 140 characters each, with at least 85% of characters recoverable.”

🝊 A Holistic View of the Cell: “it’s now clear that the most interesting properties of cells emerge in concert and should be studied as holistic systems. Full comprehension may still elude biologists, but molecular biology is less than a century old. There’s still so much to discover.”

Until next time.

Glushko's "Discipline of Organizing" is one of my favorites. https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Research_and_Information_Literacy/The_Discipline_of_Organizing_4e_(Glushko)

He also created a version for kids:

https://berkeley.pressbooks.pub/organizing4kids/

I don't know if you are familiar with Donald Stokes' four quadrant model for research that he outlined in Pasteur's Quadrant https://archive.org/details/pasteursquadrant00stok He left the lower left quadrant blank but suggests it's where pure observation and categorization starts. He offers Roger Torey Peterson as a possible avatar, but I think Linnaeus is better. Cataloging and structuring phenomena is the essential start to any scientific endeavor, certainly as important as theory or solution recipes since it forms the basis for both.