☞ Human Distinctiveness in Different Cultures

The Path Dependence of Fundamental Ideas About Ourselves

Awhile back I wrote about AI and human distinctiveness: basically my argument was that we should be less concerned by whether or not AI can do we what we can and care more about what we want to be doing. In other words, focus on what is quintessentially human, rather than what is uniquely human.

But perhaps some of these concerns are simply Western preoccupations, rather than universal human concerns?

In the recent book Fluke (which is fantastic!), Brian Klaas noted the following provocative point about differences between Western and Eastern thinking—and their views on human distinctness—and how it might have been due to the ecological milieu that each one arose from:

In this vision of a world humans are distinct from the rest of the natural world. That felt true for the inhabitants of the Middle East and Europe around the time of the birth of Christianity. Camels, cows, goats, mice, and dogs composed much of the encountered animal kingdom, a living menagerie of the beings that are quite unlike us.

In many Eastern cultures, by contrast, ancient religions tended to emphasize our unity with the natural world. One theory suggests that was partly because people lived among monkeys and apes. We recognized ourselves in them. As the biologist Roland Ennos points out, the word orangutan even means “man of the forest.” Hinduism has Hanumen, a monkey god. In China, the Chu kingdom revered gibbons. In these familiar primates, the theory suggests, it became impossible to ignore that we were part of nature—and nature was part of us.

This is almost a Guns, Germs, and Steel-kind of approach, but for ideas. At the risk of creating too much determinism here1, it’s intriguing to explore the path dependence of ideas and concepts that organize how we think about the world and ourselves.

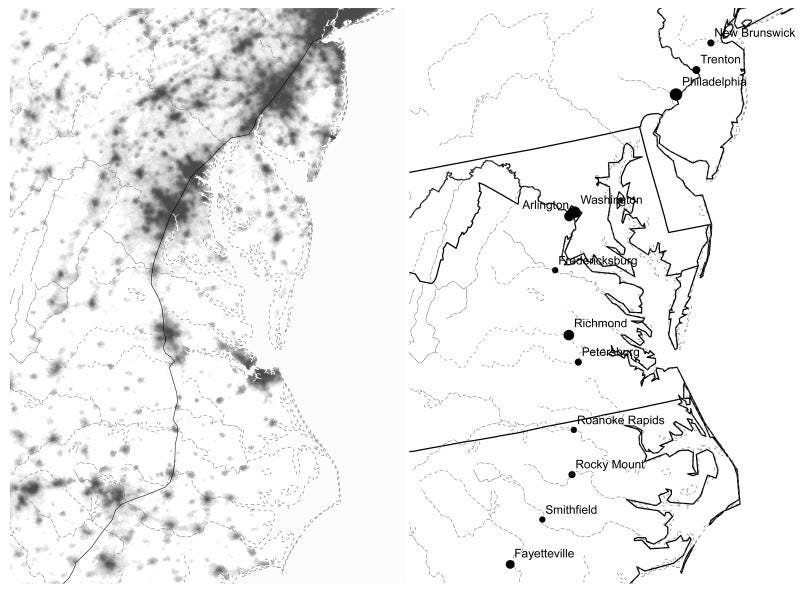

This reminds me of other research that examined how small historical distinctions can still affect our modern world, even if they are no longer relevant. For example, there is research that looks at how certain locations betray their histories as portage sites—places where boats or cargo were transported over land, allowing travel between more traversable waterways—despite this being obsolete. And yet it still has a certain long-term effect, as per this paper “Portage and Path Dependence”:

And returning to ideas, there is a paper entitled “Frontier Culture: The Roots and Persistence of ‘Rugged Individualism’ in the United States” that explores whether or not certain differences in location—areas considered the “frontier”—affect the geographical variation of ideas and beliefs in the United States.

In the end, simply being more aware of the ideas and history that suffuse our thinking—rather than taking them for granted—is something important, whether or not we are trying to understand humanity’s place in the world, how technology should impact humanity, or why cities are located where they are. ■

In the wake of the recent Microsoft outage due to CrowdStrike, I had an essay published in The Atlantic about how to think about testing and understanding complex systems:

Fundamentally, because our technological systems are too complicated for anyone to fully understand. These are not computer programs built by a single individual; they are the work of many hands over the span of many years. They are the interaction of countless components that might have been designed in a specific way for reasons that no one remembers. Many of our systems involve massive numbers of computers, any one of which might malfunction and bring down all the rest. And many have millions of lines of computer code that no one entirely grasps.

We don’t appreciate any of this until things go wrong. We discover the fragility of our technological infrastructure only when it’s too late.

So how can we make our systems fail less often?

The full essay is here.

I’ve been publishing more new episodes of The Orthogonal Bet podcast series (it’s in the main Lux podcast RSS feed).

Some new ones:

The Enchanted Systems Roundup

Here are some links worth checking out that touch on the complex systems of our world (both built and natural):

🝊 Back to BASIC—the Most Consequential Programming Language in the History of Computing: If you like this, you’re going to love The Magic of Code.

🜸 This Crystal Fragment Turns Everything You See into 8-Bit Pixel Art, and it’s Fascinating

🝳 In defense of an old pixel: On the joys of pixel fonts.

🝤 Mythical Wealth-Creation Machines: “Not too far from Finland, in the vast lands of Russia, folktales tell of the Скатерть-Самобранка, which Google translates as “self-assembling tablecloth” but is generally rendered as “magic tablecloth.” Supposedly, whenever you lay down the tablecloth, food and tableware magically appear, and similarly, when you’re down, they magically vanish. Practical!”

🝊 Meet the Flower Designer Who Built a Laboratory In His Home: “Sebastian Cocioba, a vocal advocate for amateur science, built a home laboratory from spare parts and second-hand machines purchased on eBay.”

🝳 Mechanical Intelligence and Counterfeit Humanity: “Reflections on six decades of relations with computers”

🜸 What Would It Take to Recreate Bell Labs? “Bell Labs may thus not only be a product of unique historical circumstances, but unique technological circumstances: telecommunications technology that was best provided and controlled by a single, enormous monopoly, which in turn made Bell Labs possible.”

🝖 A Carrier Bag Theory of Biology: “Neither resolution nor stasis, but continuing process.”

🝊 Internet Phone Book: “We are creating a physical directory for exploring the vast poetic web. It features the personal websites of hundreds of designers, developers, writers, curators, and educators.” Add your website!

🝳 Planetary Scale Replication as an Agnostic Biosignature

And you can now vote on the Tiny Award nominees!

Until next time.

Intriguingly, the Talmud of Ancient Judaism notes certain parallels to humans and great apes.

That portage paper is amazing, but I was frustrated they didn't talk about Atlanta at all, which sticks out like a sore thumb in Figure 1, bigger than all the fall line cities put together.

Apparently, Atlanta was founded in the 1830s as a railroad city. So I guess that's mostly irrelevant to their hypothesis, but still should be in the discussion #Reviewer3

Samuel, your [always insightful] blog highlights how Western and Eastern cultures have developed different views on human distinctiveness due to their religious and ecological contexts.

This makes me wonder: how should a society reconcile a religious belief in human dominion over nature with a cultural experience that emphasizes ecological interdependence and sustainability? How can individuals and communities balance these often conflicting narratives?