The first sewing machine for the home emerged in the 1850’s. As per this essay, “The first home sewing machine was designed in 1856, and cost $125 ($2,997 in 2010 or, about the cost of a 3D printer today).”

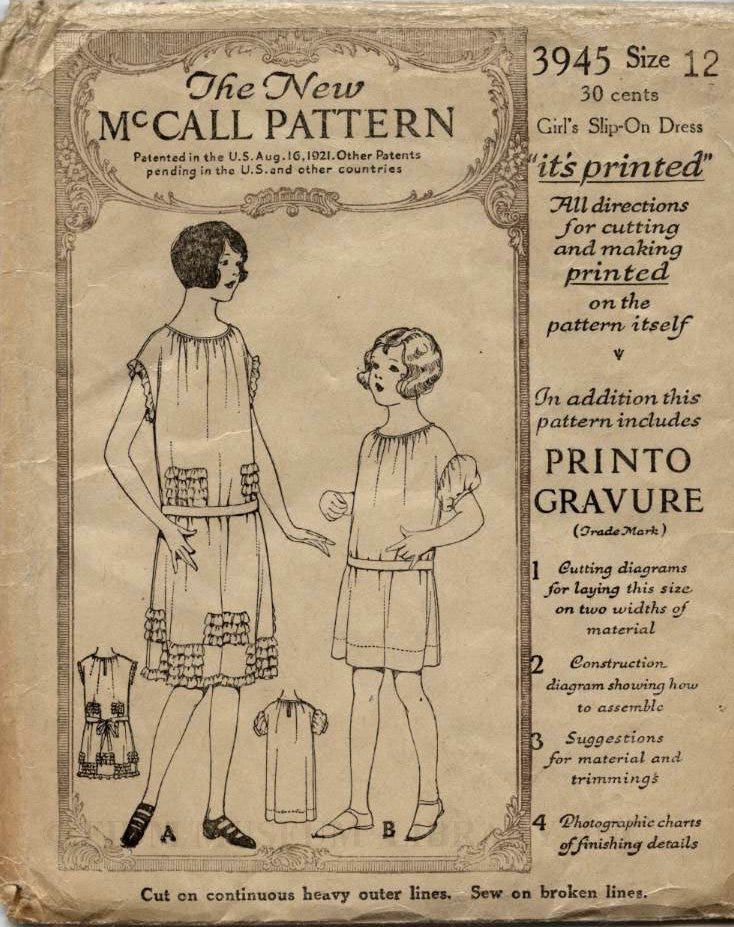

And almost immediately, people began to print paper sewing patterns that could be easily used to help sew clothes. With the work of the tailor Ebenezer Butterick, there emerged the development of graded patterns, ones that had lines allowing the person using the sewing machine to easily adapt each pattern to people of different sizes.

I find the history of sewing patterns so interesting because they were essentially selling usable bits of information. And let me make this even stranger through an unreasonable but provocative analogy: sewing machines were the personal computers of their time and sewing patterns were their software.

The sewing machine was a technology useful for a wide variety of purposes. You could make a dress, or a suit, or a pillow. And it was finally available for use within one’s own home. But you still needed to know how to design a garment; without a pattern, it’s not nearly as useful. Of course, as a user, there is theoretically no barrier to simply coming up with your own pattern; you could be a hobbyist user. Nevertheless, the ability to exploit pre-existing designs meant that you could also be a user of the sewing machine without having to worry about the design process itself. The existence of designs made this personal machine much more useful.

And of course, this kind of design work involved effort and resources. In much the same way as Bill Gates noted in his “An Open Letter to Hobbyists” in 1976, there is a cost to creating these designs:

The Butterick Publishing Company—the software company equivalent here, which published and sold sewing pattern designs—was quite successful. As per Wikipedia, “By 1876, E. Butterick & Co. had become a worldwide enterprise selling patterns as far away as Paris, London, Vienna and Berlin, with 100 branch offices and 1,000 agencies throughout the United States and Canada.”

To be clear, software and sewing patterns are not the only examples of this sort of executable information that can be created and licensed. For example, there is sheet music (as well as the rolls used for player pianos).

There were also the cards used to encode textile patterns with Jacquard looms (which were an influence in the early history of computer programming1):

The mechanism involved the use of thousands of punch cards laced together. Each row of punched holes corresponded to a row of a textile pattern. This modification not only introduced greater efficiency to the weaving process, allowing the weaver to produce, unaided, fabrics with patterns of almost unlimited size and complexity, but also influenced the future development of computing technology.

Returning to sewing machines and sewing patterns, not only did personalization arise, but the very adaptation to new technology was vital:

Butterick, unlike European tailors, embraced the new technology – in France sewing machines installed in 1840 to make uniforms for the French army were destroyed by tailors fearful of a future in which mechanized tailoring threatened their livelihoods and, for some years it was women who saw the many possibilities of sewing machines despite their high cost.

In our modern era, sewing, personal computers, and patterns have even merged more explicitly, such as through Ditto, a digital sewing pattern generator tool.

If any of you know more about this history or other interesting parallels between computing and sewing—for example, how “personal” were the early sewing machines?—I would love to know more. ■

The Enchanted Systems Roundup

Here are some links worth checking out that touch on the complex systems of our world (both built and natural):

🜸 Microchips Turn Sand Into Mind: “The surface of a perfectly polished silicon wafer cannot be felt. The skin on our salty fingertips is among the most sensitive in nature, after only crocodile and alligator faces, and the mechanoreceptors on the ends of our fingers respond to discontinuities as small as 13 nanometers. But a silicon wafer is polished free of all blemishes, including sub-nanometer ones.”

🝳 Until 3183 A.D., This Public Sculpture Is a Work in Progress: “Perhaps future generations will daub colors or make carvings, for instance — but any predictions would be about as accurate as a Wemding citizen from 793 A.D. trying to imagine the town today.”

🝖 Simulating History with ChatGPT: “The Case for LLMs as Hallucination Engines”

🜹 To Navigate the Age of AI, the World Needs a New Turing Test: “What will it mean to recognize and respect whatever degree of humanity is present in the intelligences that we ourselves create?”

🝊 Innovation: “As a project, to do it justice, this is more akin to a PhD thesis than a wonky blogpost, and without an easy outtake, but one thing that stands out starkly is how quickly we are able to create new things once a) existing innovations are distilled and we learn from them, and b) once we’re able to let them intersect with each other.”

🜸 Evidence for the earliest structural use of wood at least 476,000 years ago

🜚 River: “a visual connection engine”

🝳 Biomaker CA: “a framework for generating complex plant-like lifeforms that need to survive and evolve in user designed worlds”

🝖 “Champagne for my real friends” and Natural Language Processing: “Here’s how I tricked the computer into coming up with more champagne phrases like this, using natural language processing tools”

Until next time.

A further exploration of this history, along with a discussion of the earlier loom by Basile Bouchon, can be found in You Are Not Expected to Understand This: How 26 Lines of Code Changed the World.

Hi, Fashion historian and textile conservator here. I'm not sure the analogy works because sewing patterns existed long before sewing machines were invented. The sewing machine didn't manifest home sewing, instead it facilitated it. Sewing patterns absolutely came first, maybe not mass produced the way Butterick did, but they were distributed and shared and of course made at home. As you know, historians have long considered Jacquard looms to be an early computer, with the accompanying punch cards serving as proto-software. Punch cards did not exist until after the jacquard loom was invented, which to me makes them much more like software than sewing patterns.

sewing machine : personal computer as Jacquard loom : mainframe ?