☞ Living with the Veil of Progress

Incremental Humanism and How to Live in Our Complex World

As many long-time readers know, I am a big fan of alternate histories. One of the features of these stories is that they allow us to see how small changes—including individual choices—can ripple outwards and make a difference. If we did something somewhat different, perhaps the trajectory of our society would be profoundly changed. This is something that many of us want to feel: that our choices and decisions have an impact on others and on the world as a whole.

On the other hand though, there is the fact that it is very difficult to know the impact of our choices. When it comes to the realm of ethics, this is the problem identified as as moral cluelessness, that it is incredibly difficult—or even entirely impossible—to know the very long-term ramifications of our actions, and whether they will create more good than bad. As per the philosopher James W. Lenman:

The Universe is just way, way too big, the future ramifications of at least many of your actions way too vast for us to have even the faintest idea what actions will cause more good to exist than any other, not just proximally but in the very very long term, from now to the heat death of the Universe.

But just as there is a certain amount of moral cluelessness in the ethical effects of our behavior (more on that here), this is also relevant in how we think about scientific and technological progress. First of all, there is a decent amount of contingency in the paths that technological innovation:

…if we replayed the tape of human history, we would find that the sequence, timing, and (sometimes significant) details of inventions could be quite different, but that the main technological paradigms we discovered would also be discovered there. We would find steam power, electricity, plastics, and digital computers. But we wouldn’t find qwerty keyboards; we might not find keyboards at all. It’s tough to quantify this kind of thing in any meaningful way, and of course we can never know for sure, but my suspicion is that the technology of an alternate history of humans would look about as different from our own as the flora and fauna of Central Asia look from the flora and fauna of the central USA.

So when it comes to innovation, we forever live behind a Veil of Progress. This Veil prevents us from not only understanding the possible positive visions of the future that might win out, but even grasping how different technologies might recombine for further innovation. There is a certain fogginess towards the innovative future that we live within.

Technological and scientific progress is often thought of in terms of tech trees, those Civilization-style branching guides to how one technology or idea leads to another:

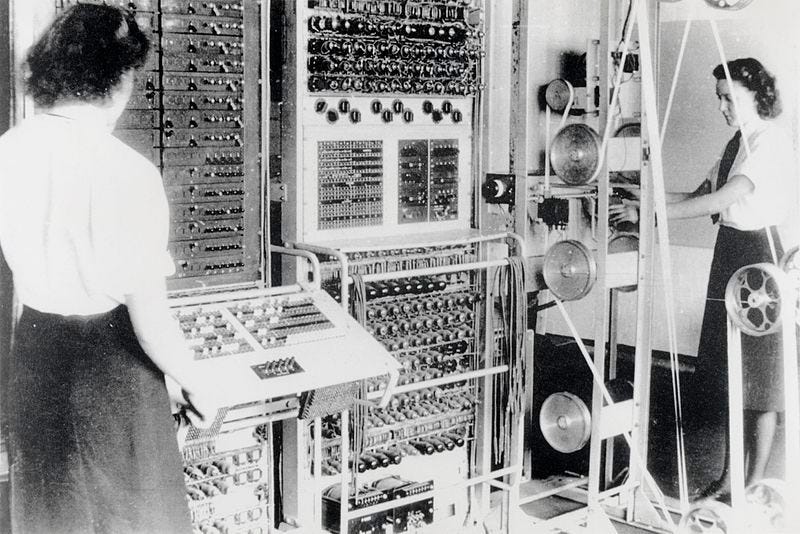

These tech trees show the interdependencies between inventions and advances. While these are satisfying to look at and help provide insight into progress, they might be most useful either for near-term decision-making—before the Veil prevents us from understanding the more distant ramifications of inventions—or simply understanding innovation after the fact. This is because often technological advances and new ideas interact and cross-pollinate in ways that we can’t possibly imagine or predict. For example, vacuum tubes were initially developed for entirely non-computing electrical uses many decades before digital computers even existed.

As per Kenneth Stanley and Joel Lehman in their book Why Greatness Cannot Be Planned—which is also my source for the vacuum tube example—in a high-dimensional search space, aiming towards an objective will not work. Instead, it is best to develop novel stepping stones that can be productively recombined.1 This expanding of the adjacent possible is a much more effective strategy.

So how should we operate if we are constantly living behind the Veil of Progress? It requires humility and incremental tinkering.

Incremental Humanism

The idea of humanism consists of, according to Sarah Bakewell, “free thinking, inquiry and hope.” But there are also other facets, from a sensibility of moderation, to a focus on improving the world.

I think incrementalism is also a key feature of humanism. As Adam Gopnik noted in his book A Thousand Small Sanities about liberalism: “Whenever we look at how the big problems got solved, it was rarely a big idea that solved them. It was the intercession of a thousand small sanities.”

This approach, of incremental humanism, is also a necessary part of the ideals of progress. Imagining a better future and incrementally improving towards this, even in an undirected manner, is the way of managing the veil of progress. As Rabbi Tarfon noted in the Talmud, “It is not your duty to finish the work, but neither are you at liberty to neglect it.” We are part of a long chain of improvements, all part of a tech tree that we can’t see and which involves a balance of innovation and maintenance (for we must preserve what we already have if we hope to be able to build on what has come before us). Revolution is the quick bandage that sounds appealing, but don’t be led to think it will necessarily result in enduring change. Big ideas can be seductive, but incremental change is the only way to live under uncertainty.2

Living in a complex world where one’s impact is difficult to fully know requires an incremental humanism. This means having a vision of the future, but a more gradual and piecemeal one. This also means having a certain amount of long-term humility. This is the best way for living with the Veil of Progress. ■

The Enchanted Systems Roundup

Here are some links worth checking out that touch on the complex systems of our world (both built and natural):

🜸 We've Made Some Metascience Progress Since 1910, but Not Enough

🝳 Evaluations are all we need: “On analysing talent in LLMs”

🝳 This Is What Happens to All the Stuff You Don’t Want: “Reverse logistics is, in some sense, the process of unwinding those abstractions—of turning ideas and possibilities back into physical goods that must be dealt with.”

🝤 Multicellularity arose several times in the evolution of eukaryotes: “convergent evolution resulting from similar selective pressures for forming multicellular structures with motile and differentiated cells is the most likely explanation for the observed similarities between animal and dictyostelid cell-cell connections”

🜹 Jason Kottke’s list of “52 Interesting Things I Learned in 2023”: Includes “Baby scorpions are called scorplings.”

🝊 Figuring out the size of a molecule in 1890

🜸 Colorado Is Not a Rectangle—It Has 697 Sides: “The Centennial State is technically a hexahectaenneacontakaiheptagon.”

🝊 The weird and the wonderful in our Solar System: Searching for serendipity in the Legacy Survey of Space and Time: “We train a deep autoencoder for anomaly detection and use the learned latent space to search for other interesting objects”

🝳 The unimagined orange and new frontiers in management consultancy: Matt Webb on ternary plots.

🝊 The D&D Alignment Chart of “How to Get a Theorem Named After You”

🜹 There Is No Planet B (For Worldbuilding): “Tolkien’s mythical Middle-earth is a relatively unchanging world over thousands of years, consisting of half a dozen countries and perhaps a hundred settlements known by name, with the theoretical population of a medium-sized medieval country. That’s not complex. That’s not vast, not infinite. It’s a simple world, a mere backdrop to stage a cool story.”

Until next time.

This also involves delving into the history of technology, finding ideas that might have been passed by but could still be useful. Here’s something I wrote about the importance of knowing technological history.

Incremental change also can feel much more tractable (and even more satisfying). As per Rebecca Solnit, “Distance runners pace themselves; activists and movements often need to do the same, and to learn from the timelines of earlier campaigns to change the world that have succeeded.”

Once again, Samuel, a really sharp blog article with great and useful substance. Reading your article made my unscientific mind reflect on when I came across the word "Kaizen." Out of necessity, I was drawn to the approach of small, incremental improvement. Since discovering it, Kaizen has become a fundamental approach in my coaching [soft skills and personal growth]. Indeed, there are those who can take on big problems or make big changes in their life/work as if there is no tomorrow and seemingly succeed. But most cannot. In fact, many get overwhelmed at this prospect. Enter the practice of "incrementalism." Yes, have a vision to guide you, but to your GREAT point...have "a more gradual and piecemeal one."

I'm less certain about incremental "humanism," though. I don't want to misunderstand your point...but for some/many, humanism connotes "without God" or spirituality. I do get that the word places emphasis and value on the human element (rational thinking, etc.). But for many, the concept of God is a source of hope. Therefore, in my mind, the two are not mutually exclusive. To be sure, I don't know nor suggest that this is YOUR belief; I'm just thinking out loud. ;)

As always, a great and thought-provoking read. Thank you!