☞ The Messiness of Reality and Stories

The balancing act between order and disorder in how we think about the world

Matt Webb recently wrote a delightfully provocative blog post, titled “When kids books low-key break the system of the world,” about the unexplainable and weird in fictional worlds, from children’s stories to the presence of Tom Bombadil in the world of Tolkien. As he notes:

The real world doesn’t fit neatly together. The real world contains the unexplained.

Therefore a real fictional universe must contain the unexplained too. Is that it?

Not the kind of unexplained that preoccupies everyone inside the fictional world, not like that, not a mystery. Rather: a magical nonsense which is a nonsense only to the reader, something that doesn’t fit even given our omniscient point of view, but the characters of the inner reality respectfully take it for granted.

This all reminded me of something I explored in my book Overcomplicated on the “biological” and messy nature of reality. The world is not all simple mathematical curves or straight lines. It is complicated and delightful, and often does not fit into our neat categories. The world is full of edge cases. As James Somers wrote about biology, “It’s all exceptions to the rule.”

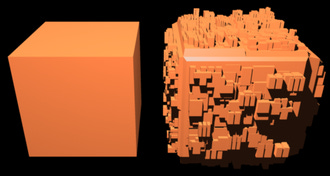

And we intuitively recognize this fact. For example, when movie effects artists and model designers need to make science-fictional spaceship models, they often employ greeblies or greebles: adding little bits and doodads to a smooth surface, such as from model kits. These greeblies just feel more realistic:

But the best discussion of this feature of the world is probably found in Neal Stephenson’s Cryptonomicon, in an exploration of the ancient Greek pantheon of gods:

Which brings me to the second basic observation, which is that the Gods of Olympus are the most squalid and dysfunctional family imaginable. And yet there is something about the motley asymmetry of this pantheon that makes it more credible. Like the Periodic Table of the Elements or the family tree of the elementary particles, or just about any anatomical structure that you might pull up out of a cadaver, it has enough of a pattern to give our minds something to work on and yet an irregularity that indicates some kind of organic provenance—you have a sun god and a moon goddess, for example, which is all clean and symmetrical, and yet over here is Hera, who has no role whatsoever, except to be a literal bitch goddess, and then there is Dionysus who isn’t even fully a god—he’s half human—but gets to be in the Pantheon anyway and sit on Olympus with the Gods, as if you went to the Supreme Court and found Bozo the Clown planted among the justices.

There is a balance here that must be followed. We need order, but we also need a bit messiness (get the balance wrong though, and we end up with pareidolia). And that’s the key to constructing something realistic.

As G. K. Chesterton wrote of the world and its complexity and rationality (quoted in Thinking in Systems):

The real trouble with this world of ours is not that it is an unreasonable world, nor even that it is a reasonable one. The commonest kind of trouble is that it is nearly reasonable, but not quite. Life is not an illogicality; yet it is a trap for logicians.It looks just a little more mathematical and regular than it is.

How do we model all of this? Humbly and with a certain amount of tradeoffs, avoiding the Kitchen Sink Conundrum.

As Alan Jacobs has written about William Blake’s illustration of Isaac Newton (artwork is here and shown below):

…his portrayal of Isaac Newton—tautly muscled, gloriously beautiful, applying his compasses to paper, but also turning his back on the irregular complexities of the natural world. Indeed, his own beauty exemplifies those complexities: he has been made by a God whose preferences in geometry are quite different from Newton’s own. A human body is proportionate and exhibits bilateral symmetry, but, the circle Leonardo drew around his Vitruvian Man notwithstanding, you can’t do figure drawing, or even sketch a pile of rocks, with a compass. Newton preferred regularity to irregularity, simplicity to complexity, but that preference took him away from reality.

Subjecting the world to rationality and rules is important and insightful. But it’s also vital to recognize exceptions and a bit of messiness, both in how we build our models and how we think about reality.

Humans seem to recognize this balance between order and disorder as something that it is a fundamental feature of the cosmos. The world is fractal and replete with edge cases. And good stories require these features as well. ■

Speaking of storytelling and world creation, I recently came across this list of nonfiction books that could be role-playing game sourcebooks. I love this idea:

Most people read fiction for the stories. But there’s a select group, you know who you are, who get as much or more joy from the “world building.” You might be in this group if you read Tolkien’s appendices to The Lord of the Rings, or if you enjoy idly illustrating (or generating) maps of imaginary kingdoms, or if you like coming up with your own stories that take place in the world of your favorite authors. There’s a whole category of people who read the manuals and source books for tabletop role-playing games, not because they intend to play them, but because they like luxuriating in the descriptions and imagining the alien worlds they portray.

What if I told you that you could have this experience in the real world as well? Our universe is fractally strange, and so are our societies. This is a post dedicated to works of non-fiction which, if you close your eyes or change the names, give the same imaginative thrill as the most daring speculative fiction.

We need more of these! And we also need more infodumps. As per a short essay I wrote years ago on “Pocket Histories of Interstellar Societies”:

I’m a fan of science fiction. But as much as I enjoy the ideas and the storytelling, when it comes to grand interstellar societies—galactic empires, federations, and all that—one of the things I love the most is to simply read the histories of these worlds. A capsule summary of how a world came to be—technologies invented, geopolitical shifts, how it ticks and operates, and the current state of that universe—is my catnip. Don’t get me wrong, I love reading the stories that are placed in these settings too, but I am also a big fan of simply learning about how these these vast interstellar settings for humanity are constructed.

The equivalent of this for the real world that I provided was the CIA World Factbook. But we need more of these for nonfiction and I’m glad that people are trying to create—and highlight—this kind of writing.

(A bit of self-promotion: my forthcoming book is a field guide of sorts to the many delights and features of computation, as well as how this all relates to the world more broadly.)

The Enchanted Systems Roundup

Here are some links worth checking out that touch on the complex systems of our world (both built and natural):

🜸 The Turing Test and our shifting conceptions of intelligence: ‘It remains to be seen if Turing’s prediction is merely off by a few decades, or if the real alteration will be in our conceptions of what “thinking” is—and our realization that intelligence is more complex and subtle than Turing, and the rest of us, had appreciated.’

🝳 The Decline in Writing About Progress: “The rise and fall of our interest in progress?”

🝤 Dwellers in the Deep: Biological Consequences of Dark Oxygen: “Our findings indicate that complex life fueled by dark oxygen is plausibly capable of inhabiting submarine environments devoid of photosynthesis on Earth, conceivably extending likewise to extraterrestrial locations such as icy worlds with subsurface oceans (e.g., Enceladus and Europa), which are likely common throughout the Universe.”

🜹 Piecing Together an Ancient Epic Was Slow Work. Until A.I. Got Involved: ‘Scholars have struggled to identify fragments of the epic of Gilgamesh — one of the world’s oldest literary texts. Now A.I. has brought an “extreme acceleration” to the field.’

🜸 Predictions from Tom Wolfe in 1987: “The twenty-first century, I predict, will confound the twentieth-century notion of the Future as something exciting, novel, unexpected, or radiant; as Progress, to use an old word.”

🝖 An Intoxicating 500-Year-Old Mystery: “The Voynich Manuscript has long baffled scholars—and attracted cranks and conspiracy theorists. Now a prominent medievalist is taking a new approach to unlocking its secrets.”

🝊 Slow Roads: A “procedurally-generated driving game”

🝳 The Dying Computer Museum: “I want to refocus to the fact that the Living Computer Museum was never a museum.”

🜹 Ode to Man: “It is unfashionable to express reverence for humans—but no entity in the universe deserves it more. A species with this capacity for science and art, for inventiveness and creativity, for planning and building, for love and compassion, profoundly deserves to live, to thrive, and to expand to the planets and the stars.”

Until next time.

> Speaking of storytelling and world creation, I recently came across this list of nonfiction books that could be role-playing game sourcebooks. I love this idea:

I absolutely love this list!! I want to see thousands more books like this. It's a whole genre. It reminds me of a few things:

(1) telling the story of the rise of AI through our captchas, how increasingly complex they have gotten in the last ~2 years, as the list of things humans can do and AI cannot shrinks

https://x.com/DefenderOfBasic/status/1772589955509891453

(2) taking snippets from magazines about culture, intermixing them with fictional ones, and see if the reader can tell, what is real articles about our world, and what is fictional

https://x.com/DefenderOfBasic/status/1801612865079542117

Oh, do I have some fun talks to share about Dionysius making Apollo take a swerve. I mean, about storytelling in videogames.

Before you Fix a Leak, Ask if it's a Fountain (Jason Grinblat, 30min)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kvCky6BbTuE

Topological Analysis of Open-Endedness in Video Games (Lisa Soros, 15min)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kx_88xkMdX8

In response to Webb - the greebling is called a clinamen, in literary theory. I enjoy Calvino's use of it in Six Memos for the Next Millennium.